December Updates: On Spending Time

Dear Readers,

It’s been a while since I last wrote. It’s been more difficult than usual to motivate myself to write lately(or do anything for that matter). I don’t know how much longer I can excusably say that I’m mentally exhausted from the pandemic. It might just be me this time. But I’ve been wanting to write to reflect on work from this Fall, so I’m going to try my best to assemble what’s been swimming around in my head in bits and pieces. I’ll break up this post into two parts. The first will explain what I did, and the second will reflect on the work itself.

After my last iteration of my machine learning/family photo project, I knew that if I walked in your footsteps, it would become a ritual, I had planned on spending the Fall consolidating what I already had in terms of images and interviews and refining how this work might take form in physical space (i.e. prints, video installation, etc). I even thought I’d have space to look at building archives of other first-generation Americans’ family photographs.

But in fact, a lot of the past few months have been about taking steps backward and slowing down. There were a few unanswered questions that I still needed to address about how my model was trained. Through conversations with several amazing people including my faculty point person at ITP, Allison Parish, I realized I needed to spend more time with the data.

For one thing, I had been using a technique called transfer learning. This technique serves as a sort of shortcut by using a pre-trained model rather than training a model from scratch. In short, my machine learning model wasn’t purely trained on my own data. It was first pre-trained on a larger dataset of faces from Flickr and then trained some more on just my specific dataset of family photos. Transfer learning allowed me to work with a much smaller dataset (even 1,000 family photos is a very small dataset for a machine learning model) and meant my model would have a much shorter training time. However, this shortcut created a huge hole in the conceptual grounding of my project. I could no longer say this model was a reflection of my archive because in reality, it had other influences. In fact part of my original intention was to work in a way that you could say was directly opposed to large datasets like ffhq. I wanted to know who’s data I was using, have a personal connection to each image, and be a caring steward of this archive.

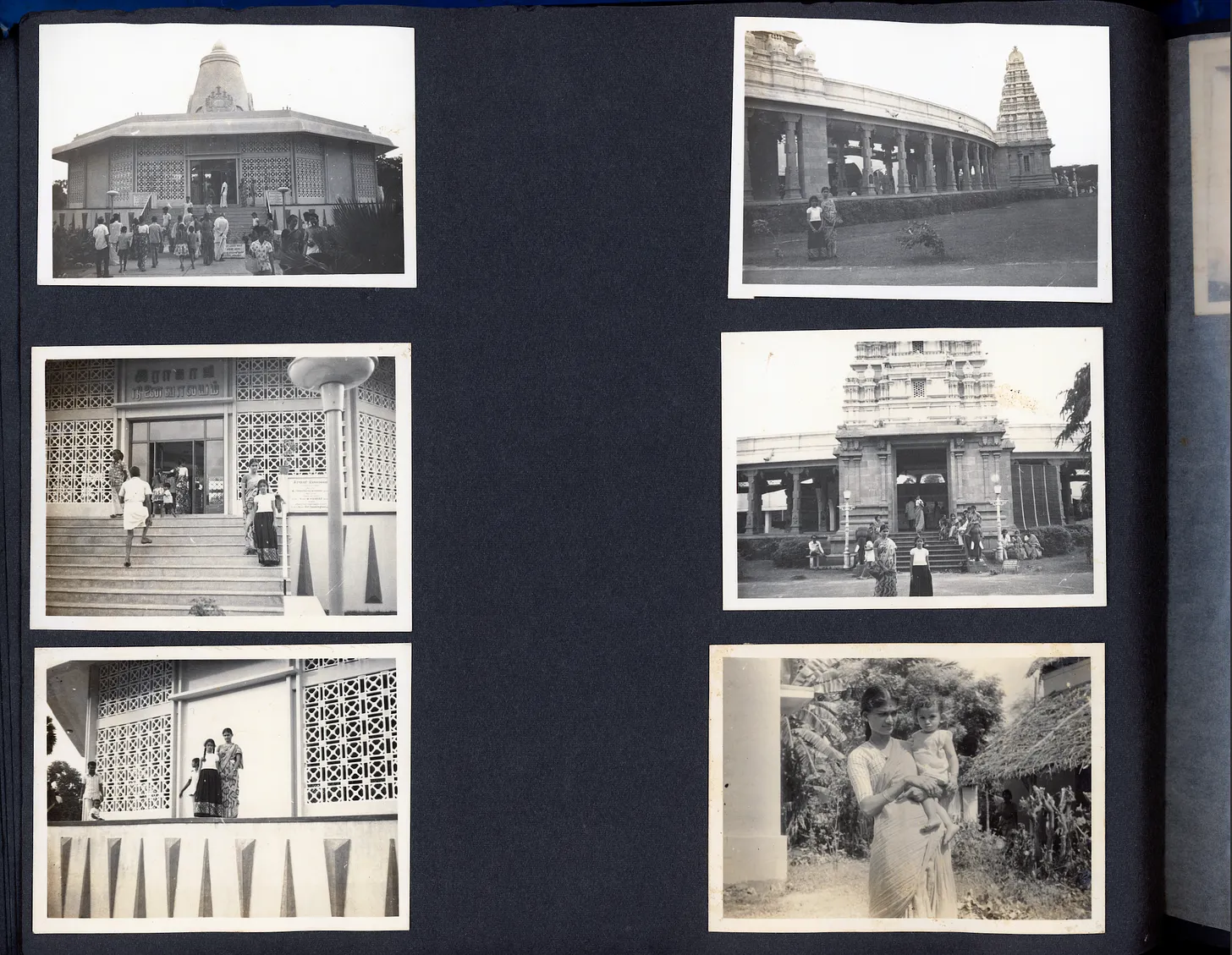

Scan from my uncle’s photo album

Scan from my uncle’s photo album

So I went back to the drawing board. I was serendipitously able to collect a good amount of additional photographs from my uncle’s album that he so graciously lent to me to scan. I also did a bit of data augmentation by duplicating my dataset and flipping the duplicates horizontally (this was a shortcut I was okay with). I then trained a StyleGAN model from scratch only on my family photographs. The results were so worth the time and effort. In all honesty the aesthetic difference in the generated images are slight and might only be something I can detect having worked so much with these images, but I still think it was worth it because I know that this model reflects my family archive. Additionally, I felt like I gained a better understanding of the technology I was using by simply spending more time with it.

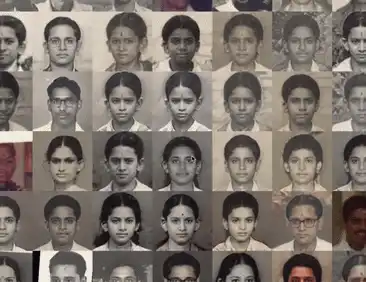

Generated images mixed in with original photographs

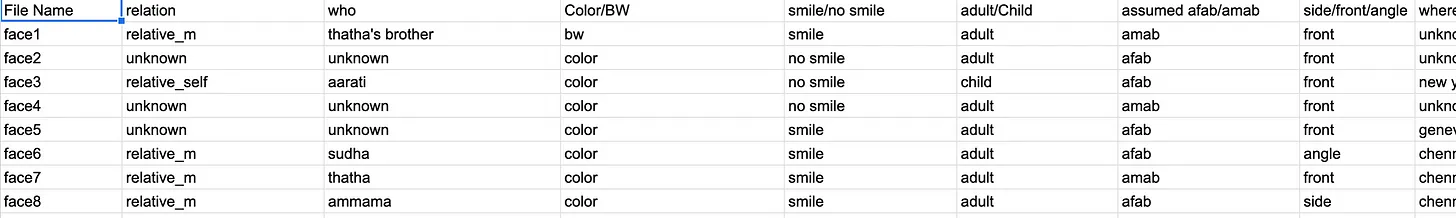

I also realized that the second thing I needed to do this Fall, was to create metadata for my dataset. This process is still in progress. But essentially, I want to be able to answer questions (without guessing) like: who is most represented in the dataset? How many people are wearing glasses? How many people are on my mother’s side vs my fathers’ side? How many people are not blood relatives? How many color photos vs black and white? These questions could only be answered by going back and one-by-one, writing down the information for each and every photograph in my archive in a spreadsheet.

Generated images mixed in with original photographs

I also realized that the second thing I needed to do this Fall, was to create metadata for my dataset. This process is still in progress. But essentially, I want to be able to answer questions (without guessing) like: who is most represented in the dataset? How many people are wearing glasses? How many people are on my mother’s side vs my fathers’ side? How many people are not blood relatives? How many color photos vs black and white? These questions could only be answered by going back and one-by-one, writing down the information for each and every photograph in my archive in a spreadsheet.

Screenshot of metadata I’m collecting for each image (the relationship, who it is, whether it’s in color or black and white, whether they are smiling etc.)

Screenshot of metadata I’m collecting for each image (the relationship, who it is, whether it’s in color or black and white, whether they are smiling etc.)

So although spending many hours in spreadsheets and code editors may not sound like a creative venture, I feel this attentiveness will really help the work. I think I had to unlearn a lot in slowing down. I’m grateful for how machine learning has pushed me to be more intentional and patient in my methodology. I find this a much needed contrast to the way I’ve worked with computational methods in the past. Working slowly feels somehow akin to my fermentation experiments going on in my kitchen. You have to be constantly checking up on them and willing to wait a long time. And even then the results can surprise you!

Some nocino I fermented (walnut liquer)

Some nocino I fermented (walnut liquer)

Always in gratitude,

Aarati