I knew that if I walked in your footsteps, it would become a ritual: Dispatches from a remote residency at Ada X

The following text was written as part of a remote artist residency with Ada X in Montreal.

I am privileged to be able to work with family photographs in my practice.1 Over the years, I’ve digitized all of these images, and along the way, tried to understand (as much as I could) the stories behind the photographs through conversations with family. Many of these photographs were gathered and brought to the U.S. (with permission) from my maternal grandmother’s house in Chennai. Some were from my paternal grandmother’s apartment in Hyderabad (scanned down the street at an internet cafe) and few were even dated back to the 1930’s. Many of them were also from my parent’s closet in upstate New York. All in all, I scanned 1,581 photos. Having looked at each and every one of these photos, I feel like my head sometimes conflates memories of these photos with the memories that these photographs attempt to document. In that way I kind of have these “inception” memories. Copies of copies of copies. And with each copy, something is lost and something’s gained.

It’s important to note that I didn’t scan these photos with the intention of using them as training data - at least not in the beginning. I started digitizing photos back when I was a teenager and first found a closet full of photos in my grandmother’s house. It was a way for me to connect with my family abroad, but also to better understand what happened before I happened. There are a lot of gaps in the story for me when it comes to my parents’ childhood and my grandparents’ childhood. My parents don’t talk much about the past, but through these images, we’ve been able to have more open conversations. I also love to point to my paternal grandmother as an example of how much has changed between our generations. She is 100 years old (her birthday was June 1st!). My grandmother lived through Indian Independence, through marriage at 12 years old, through raising 10 children, and most recently through surviving COVID-19. I’m vaccinated and admittedly these days, I walk through the park with my mask in my pocket most times while my grandmother lives still in lockdown in her home in Telangana. I’m unmarried, almost 30, and living with my white jewish partner in Flatbush, Brooklyn. There are oceans between us (literally and figuratively) but these images help me try to piece together a bridge.

Through conversations around these images, I also realized that it’s not so much about retracing exact footsteps as it is about the act itself of remembering, re-remembering, and ultimately reformulating the past. In other words, I know my understanding of the past will be inaccurate: Names are forgotten, moments documented in photographs are conflated with other ones. And for me, this is ok. I think memory is always an approximation and through approximation it becomes a generative practice. It mutates over time, over place, and over generations. This does not make it any less powerful or healing.

This idea of approximation and mutation is what draws me to work with Machine Learning.

In this work, I am primarily using a type of Machine Learning called GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks).* A GAN is made up of two different machine learning models. One is called a discriminator and the other is called a generator. To train a GAN, you might show it a large dataset of images (although you can use GANs with other types of media as well, such as text, in fact the title of this work was generated using a text-based model). The generator model will then attempt to “draw” its own version of these images, while the discriminator will try and distinguish the original images from the images created by the generator. They will go back and forth like this many times and in each exchange, the generator will get better at creating fake images while the discriminator will get better at telling the fake images from the originals.2

There is something compelling in the aesthetic of the GAN’s output. The images it produces feel ghostly, uncanny and resemble the original photographs as much as it deviates from them. This to me, feels in parallel with approximation and mutation through memory. At least for me personally, where there is so much to be imagined in what there is to be lost.

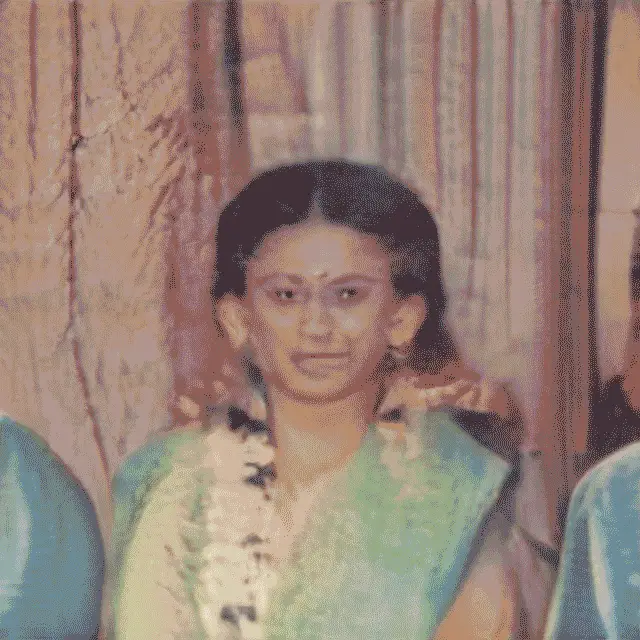

Generated images of my mom

Generated images of my mom

Generated images of my mom

Generated images of my mom

The images can also sometimes be quite rudimentary, which I find charming. Like a child’s drawing? Or maybe like a stylized painting? But they all have some sort of essence of the originals. That much is clear to me having looked through all the photographs individually.

It’s also important to point out that in the technical process, the real point of creative control or influence with a GAN is in the collection and curation of the training data. For me it has also felt like an opportunity to think about care and data. To say I’m using family photographs as “training data’’ sounds quite cold and I have been experimenting with using the term “data foraging” to try and surface notions of attentiveness and care within this process which is often experienced in the form of big data where it’s more extractive (or at least more corporate). That is not to say my process isn’t at all extractive. Obviously I’m benefiting artistically from using images of other people in my work, but I hope that I can at least motion towards a more consentful approach and an approach that intentionally acknowledges our role in machine bias.

Machine bias is a prejudice found in an algorithmic system. For example, Joy Buolamwini’s research project Gender Shades, points out that major facial recognition software has a higher margin of error when looking at faces with darker skin tones. Many established facial recognition datasets such as Labeled Faces in the Wild skew unevenly white and male making the dataset itself biased. This is where the idea of “garbage in, garbage out” comes into play. A machine learning model is only as good as what we teach it with. And of course, this leads us back to our very much human-led data collection methodologies.

I personally am of the belief that we cannot neutralize data. I think we will always influence the systems we create and so I guess I’m really of the belief that we ourselves can never be truly neutral. We can of course always be better. And we should. But I think the notion that we can have a truly unprejudiced system is dangerous because it creates a context in which automated systems can justifiably be used in place of human regulation (i.e. predictive policing) and a context in which our data is synonymous with ourselves. It also ignores the larger question of how these systems are being used and who they disproportionately impact. In other words, should I be fighting for facial recognition software to be able to see my brown face if I don’t have control of how this software is used?

Within my practice, machine bias has actually served as a kind of tool for self-reflection. On one hand, I take advantage of skewed data by purposefully segmenting my images across certain themes. In this way, I’m able to create different vignettes of memories of specific people or events (during this residency, my focus has mainly been on photos of my mother). On the other hand, unexpected machine bias has led me to notice things about my dataset that would’ve otherwise not stood out. For example, in the model that I trained on my mother’s photographs, the output images often resemble her marriage photos (where she wears a specific yellow sari with a white flower garland). This led me to realize the majority of the photos of my mother in my archive are of her wedding day. Marriage, or rather pressure to get married, has been a hot-button issue between myself and my family as of the past five years (which I’m sure a lot of desis can relate to) so of course this makes me think about the cultural weight placed on marriage especially for AFAB South Asians.

GIF of several machine generated images that resemble the marriage photos.

GIF of several machine generated images that resemble the marriage photos.

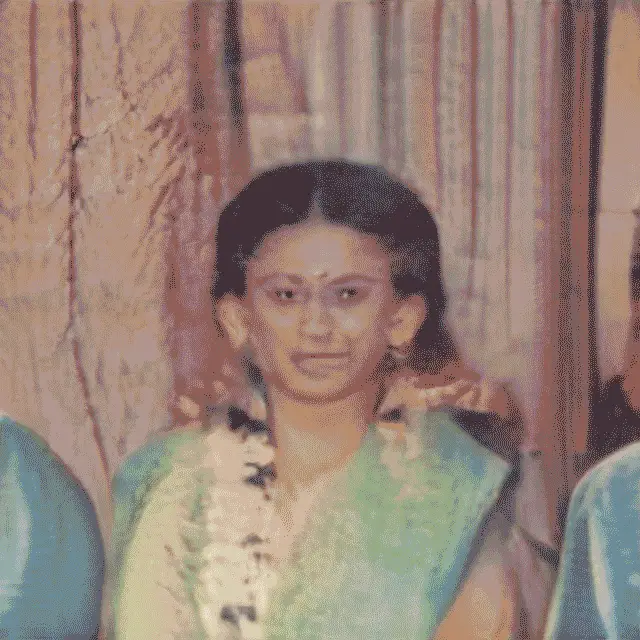

Crop from a photo of my mother during her wedding (shown here with her permission). Not sure who took the photograph.

Crop from a photo of my mother during her wedding (shown here with her permission). Not sure who took the photograph.

It does feel a bit strange to use a technology that has such strong connotations whether idealist or dystopian. But it’s my hope that I can create a small playful and healing space for working with machine memory.

In terms of consent in my process, it’s been a work in progress for sure. I always made sure to gain permission from original custodians of the photographs before digitizing and also to give my family access to digital images. Obviously my family members can share those images with whoever they want so it’s not private per say, but I’ve tried to be intentional about not posting public links to folders of images anywhere and also not releasing processed images (there is a lot of pre-processing that I do to make the images “readable” as training data such as cropping, aligning, and downsizing). There’s also the issue that many of the people in the images are unidentifiable or have since passed away. I don’t have a clear idea of how to deal with that yet.

I do make sure to share my work with my family. I don’t think they always understand what I’m doing or why I’m doing it (honestly, I often feel the same way) but they are generally supportive. I think segmenting my data allowed me to be more intentional about involving the subjects of the photographs in the art-making process. Specifically during this residency, I’ve created a machine learning model trained on just the photos of my mom. I’ve been interviewing her about the original and generated images. It’s been a great catalyst for talking through specific memories, feelings and hopes. Including her voice has added a really important dimension to the work. She is aware of my technical process and given permission for the use of her photos, her generated images and her voice recordings.

I should also say this is very new territory for me as I’ve never really conducted interviews or had such a participatory component to my work before. I’m excited and nervous about this trajectory and I will continue to share my thoughts on this process as I think it will be ever-evolving.

P.S. As I mentioned, while working with GANs, I’m interested in both what is similar and what is different to the training data. But there is a certain balance I’d like to strike to make it work aesthetically and conceptually. It’s been really entertaining to look at when my GAN absolutely failed at producing compelling images.

Here is a video (original sound from @couchtable on Tiktok) I made of some “outtakes” of generated images of myself…

- It’s important to acknowledge that having these photographs is a privilege. Having access to a camera and having access to my ancestral history is a privilege. It’s one I don’t take lightly.

- It’s important to note that the generator does not look at images like we do. It doesn’t know what eyes are for example. It is looking at the arrangement of pixels and trying to find patterns and consistencies.